Christmas Family Murders: In the Still of the Night

On the night of Wednesday, February 7, 1906, in a sleepy town in Alabama, a shocking crime shattered the stillness. Three members of the Christmas family were brutally murdered in their own home, each struck in the head with an axe before their throats were slit.

Located in the Alabama’s southeastern most county, Cottonwood, was barely a “map dot” of two to three hundred people in 1906. The town had just been chartered three years earlier. It was right over the Florida line and was known as a “whistle stop.” Trains going through would only stop on request, signaled by a whistle from the train conductor.

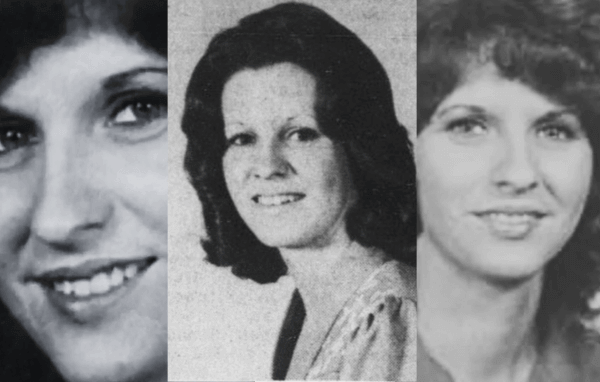

It was a quiet, rural community. One of its more prominent citizens was Jeremy M. (J.M.) Christmas. He was a Civil War veteran, well known in the area, and people considered him a man of means. He owned a business and also worked as a judge. J.M. and his wife Martha shared 13 children, seven of whom died before the age of 10. By 1906, four of their surviving children were adults and lived with their own families. Their 19-year-old son Joseph was away at school. Their youngest surviving child, 10-year-old son Slocum Gunger, still lived at home.

Christmas Family Murders: In their Own Home

When Mr. Christmas failed to appear for a planned appointment on February 8th, friends checked on his residence. They discovered J.M., Martha, and young Slocum dead in the room where they all slept, lying in puddles of blood. The killer had beaten their heads with the blunt end of an axe and slit their throats. The attacker had beaten them so severely that their heads were almost severed from their bodies. The attack was brutal and clearly case of overkill.

Police originally considered the motive to be robbery, but nothing seemed to be missing from the home. A safe in the hallway was not touched. In the room where the murders occurred, several dollars were laid out on a table, untouched. The bloody murder weapon, an axe belonging to the family, was found in the front yard of the home.

Panic engulfed the small community. Citizen posses were formed to find the killers. Within a month of the murders, several families relocated, citing fear as their reason. Newspapers called for blood, reporting, “Anger in the neighborhood is at a white heat, and no stone is being left unturned that might aid in the work of detection.” 1Anniston Star 2/11/1906

“I have an idea about this thing, but of course I can’t afford to speak of it. I might do some man a terrible injustice.” – Cottonwood resident to Montgomery Advertiser March 7, 1906

Police Work in the Early 20th Century:

As you can imagine, early 1900s police work was vastly different than today. A community such as Cottonwood would not have had its own police force. They would have to rely on the county sheriff or perhaps a town marshal. Those people would not be well trained, if at all, in conducting investigations of this magnitude. Houston County Sheriff Crawford arrived in town the day after the bodies were found. Bloodhounds were sent for, a common occurrence at the time. Unfortunately, a prolonged rain hampered their efforts. Several unnamed people were arrested following the murders, but all were able to provide an alibi.

Private investigators were common in more urban areas but not always reliable or trustworthy. They would travel to areas like rural Alabama, usually to try and receive reward money. Author Bill James says they worked mostly as spies. They’d come to a town, try and infiltrate the local criminal element, and cash in on any information they’d been able to gather. By no stretch of the imagination could their methods be called scientific.

A Preposterous Plot

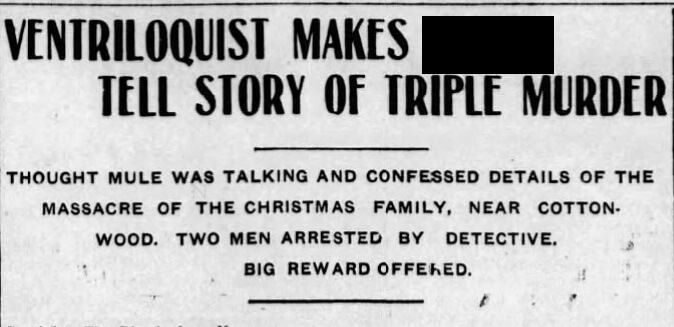

One such investigator, a man named W.C. Franklin, arrived in Cottonwood from Chicago shortly after the murders. He concocted a plan that can only be described as absolutely absurd. He hid out in some woods near Cottonwood and pretended to be an escaped prisoner from Georgia on the run from the law. He hired a Black man to bring him meals. The man would deliver the food on a donkey. Franklin had convinced himself that the man knew something about the murders, so he persuaded a ventriloquist friend to hide in the woods and “speak” for the donkey. The food delivery man was so shocked by the donkey speaking in a human voice that he immediately fell to the ground and confessed to the triple murder. He also implicated the Christmas’ oldest son, William, and one of their sons-in-law, Walter, in his “confession.”

The “investigator” and ventriloquist went to the sheriff with this outlandish tale. Inexplicably, the sheriff believed the story and on March 13, 1906, arrested William Christmas, Walter Holland, his wife Cordelia (the Christmas family’s second oldest child), along with Jasper and John Justice, the food delivery man and his father. 2 It is not totally clear, based on newspaper reports, whether John Justice was the name of the father or the son.

Dubious Tactics

As you can probably gather, back then the police could arrest someone just because they felt like it. They didn’t always require things like proof or evidence. In the post-Civil War South, Black people, especially Black men, were affected by disproportionately high arrest rates. Some estimates say that between 1880 and 1928, approximately one in every three Black men had been arrested at some point in their lives. The charges were often baseless, at times even fabricated.

The “talking donkey” story was reported in newspapers as far away as Indiana and California. William was released on bail on May 10, 1906. Walter Holland was released on bail a few days later. Cordelia was released from jail, although it is not specified when. John and Jasper Justice were kept in prison; it is unclear when they were released, if at all.

William, who had married a local woman named Minnie Buntin the year before, is the only one who would eventually be tried for the Christmas family murders. Authorities had discovered another piece of evidence against him besides the word of a terrified man who thought a donkey was speaking—a bloody shirt.

A Bloody Shirt is Found

In an April 1906 article, the Birmingham News reported that the shirt’s location was revealed to a local man in a dream.

“A man who had been endeavoring to ferret out the crime and bring the guilty party to justice and who had spent many sleepless nights in trying to solve the mystery had a dream that the shirt of the man who killed the Christmas family was hidden in the attic of an old building in the neighborhood. The next morning he got a rake, went to the house in question, went in the garret and between the ceiling of the two floors he raked out this shirt, which corresponded in color with the cuffs found in William Christmas’s trunk, the shirt of which was missing.”

Other reports state that the bloody shirt was found in the loft of the Christmas Family’s store. A man named W.L. McKinley testified in William’s trial that that’s where he found it. William’s explanation was that he had worn it while slaughtering a pig and left it at the store because his wife did not like to see blood. William declined to answer when questioned about the whereabouts of the pig.

A New Will Comes to Light

It was not reported what kind of store, or for that matter, what type of business J.M. Christmas owned. He had supposedly written to his younger son, Joseph, a “few days” 3Birmingham News 4/3/1906 before the murder and asked him to come take over the business from William. J.M. accused William of being too “wild and reckless” and of squandering the business’ money. In addition to this, J.M. had written a new will, which cut William off almost entirely.

A reportedly bloody copy of the new will was found at the office of the probate judge, three weeks after the murders. It was speculated that William originally intended on destroying the new will, but instead mailed it to the probate judge, since people in the area knew J.M. had changed it recently. The new will, authorities decided, was the catalyst for the axe murders. It does seem nonsensical that William would kill his parents and younger brother in order to destroy the new will but then end up sending it to the court anyway.

The details of the original will are unknown, but if the estate was evenly divided, William would have had to share the proceeds with his four surviving siblings, Carrie, Cordelia, Alice, and Joseph. It was not reported whether William actually retained control over his father’s business, if it was passed to Joseph, or if the two shared ownership.

Ambiguous Evidence

Other evidence against William was an alleged assassination attempt on Joe, days before the murders. Joe, who had reportedly come home to take over the family business, was shot at three times. He was not hit and survived. The perpetrators were never caught, and this charge was not mentioned in the trial records. Shortly after the murders, one of William’s sisters accused him publicly, though which sister made the claim remains unknown.

William’s reaction to the murders was also called into question. While the coroner was in the room with the bodies, William walked in, walked through the blood on the floor, and calmly rolled a cigarette and began smoking it. I would be remiss not to mention that it’s unfair to judge a person’s reactions to a loved one’s death. Unless we’ve been through it, we don’t know how we would react, especially losing three family members at one time in such a violent manner.

An Unreliable Witness Tells her Story

An accounting of a witness to the murders was given in the Birmingham News. A woman, who said she lived in the home with the Christmas family, claimed she heard the killers come into the home. Terrified, she hid under her bed. She heard both J.M. and Martha call William by name. It is unclear if the killers brought lights into the home or if there was a lamp kept burning at the home.

The killer, who was either John or Jasper, struck J.M. with the axe first. When Martha pleaded for her life, causing the attacker to hesitate, William allegedly drew a pistol and threatened his accomplice to continue the killings. Slocum was then killed in his bed, having never woken up. The bodies were covered with their bed sheets before the killers left the home.

However, this account raises several questions. It doesn’t explain the multiple axe blows or the victims’ slit throats described in other reports. In addition, this version of events is absent from other contemporary newspaper accounts and is not mentioned in a later trial synopsis. It’s unclear if this story is true or an embellished tale by a newspaper seeking to boost sales.

The Trial Starts

William Daniel Christmas went to trial on November 19, 1906. Witnesses recalled hearing the sound of a horse on the road leading to the Christmas family home on the night of the murders. Buggy tracks were discovered near the house, but Jim Brown, a longtime neighbor, reported seeing only a horse and rider—no buggy in sight. Brown, despite knowing William for years and having sufficient light to do so, was unable to identify the rider as William. It’s unknown what time this sighting occurred since the murders were thought to have happened late at night.

Christmas’ attorney, Mr. Price, threw doubt on the blood-spattered will and the bloody shirt. Both had been taken by Sheriff Crawford for further testing. The shirt went to Jacksonville, Florida, but no results were submitted to the court. The will went to New Orleans, Louisiana, but again, no results were submitted.

The coroner’s jury, which was impaneled the day after the murders, had opened the safe and gone through every piece of paperwork inside. If the will was indeed bloody, surely they would have put it in their final report.

The jury, made up of 12 white men, deliberated for 60 hours. A mistrial was declared on November 26, 1906.

Aftermath of the Christmas Family Murders

William continued to live in Houston County until the mid-1930s, when he and his wife, Minnie, moved to Miami, Florida. He passed away on September 29, 1941, after a long illness. He was survived by Minnie, two of their daughters, and his brother Joseph. William was buried at the Woodlawn Park North Cemetery and Mausoleum in Miami. The Christmas family murders remain unsolved to this day, more than a century later.

More Carnage

The Christmas family murders were not the only brutal axe murders committed that decade. Several similar massacres had occurred in the southeastern United States and beyond.

Nine members of the Acreman family were killed with an axe in Allentown, Florida, on May 14, 1906.

Five members of the Lyerly family were killed in Barber Junction, NC, on July 14, 1906.

Six members of the Moore family, along with two visiting members of the Stillinger family, were murdered in Villisca, Iowa, on June 9, 1912.

Between May 1918 and October 1919, six people were killed and six more injured in the New Orleans, Louisiana area by the infamous Axeman.

The Man from the Train

Authors Bill James and Rachel McCarthy James connected over 50 separate incidents of axe murders of families to one man in their book, The Man from The Train. These include all of the axe murders mentioned above, with the exception of the Axeman of New Orleans. Their suspect, a German immigrant named Paul Mueller disappeared into Germany sometime after 1922.

Sources:

Associated Press. Triple Murder near Alabama Town. Pensacola News Journal. 08 February 1906.

Family Found in Pool of Blood. Birmingham Post-Herald. 08 February 1906.

Horrible Deed at Cottonwood. Dothan Eagle. 10 February 1906.

Man, Wife and Child put to Death. The Troy Messenger. 14 February 1906.

Jury Could Not Reach Verdict. Pensacola News Journal. 27 November 1906.

Christmas on Trial for Triple Murder. The Birmingham News. 03 April 1906.

Two More Arrests Made. The Selma Times. 16 March 1906.

Negro and a Mule: Medium Through Which Murder Mystery is Solved. The Canebrake Herald. 22 March 1906.

An Alabama Sensation. The Marion Times-Standard. 22 March 1906.

Nothing Yet Done: No Arrest for Murder of the Christmas Family. The Montgomery Adviser. 07 March 1906.

Big Rewards are Offered. The Canebrake Herald. 15 February 1906.

Ventriloquist Makes Negro Tell Story of Triple Murder. The Birmingham News. 15 March 1906.

Will Christmas on Trial. The Elba Clipper. 06 April 1906.

Slayers Rode in Buggy. The Canebrake Herald. 22 February 1906.

People’s Anger at White Heat. The Anniston Star. 11 February 1906.

No Arrest for Murder: Search Continues for Christmas Slayers. The Montgomery Advisor. 11 February 1906.

Find A Grave: Jeremiah M. Christmas

Find A Grave: Slocumb Gunger Christmas

The Cherokee Advance Newspaper February 16, 1906

A huge thank you to Cindy Sloan for her tremendous work at Find a Grave.

All historic newspapers accessed via Newspapers.com except where noted.

Featured Image is by Dorothea Lange of an Alabama cotton farm in 1938, accessed via the Library of Congress.

- 1Anniston Star 2/11/1906

- 2It is not totally clear, based on newspaper reports, whether John Justice was the name of the father or the son.

- 3Birmingham News 4/3/1906