The Carroll A. Deering: What Happened to its Crew?

The Carroll A. Deering, an abandoned ship was discovered on the treacherous Diamond Shoals in North Carolina in January 1921. Twelve men disappeared into the wide ocean expanse. The only living souls found on the ship were three six-toed cats. The mystery of what happened to the crew of the Carroll A. Deering remains unsolved more than a century later.

- The Construction and Early Life of the Carroll A. Deering

- The Voyage Starts out Troubled

- The Voyage Continues

- The Disappearance that Captured a Nation

- The Treacherous Diamond Shoals

- A Ghost Ship

- The Disappearing Crew

- The Search for the Vanishing Crew Begins

- The Government Steps In

- Trouble at Sea

- Message in a Bottle

- A Cruel Hoax

- Investigation Concluded, but not Closed

- Theories about the Carroll A. Deering

- The U.S.S. Cyclops

- The S.S. Hewitt

- The Aftermath

- A Century of Silence on The Carroll A. Deering

The Construction and Early Life of the Carroll A. Deering

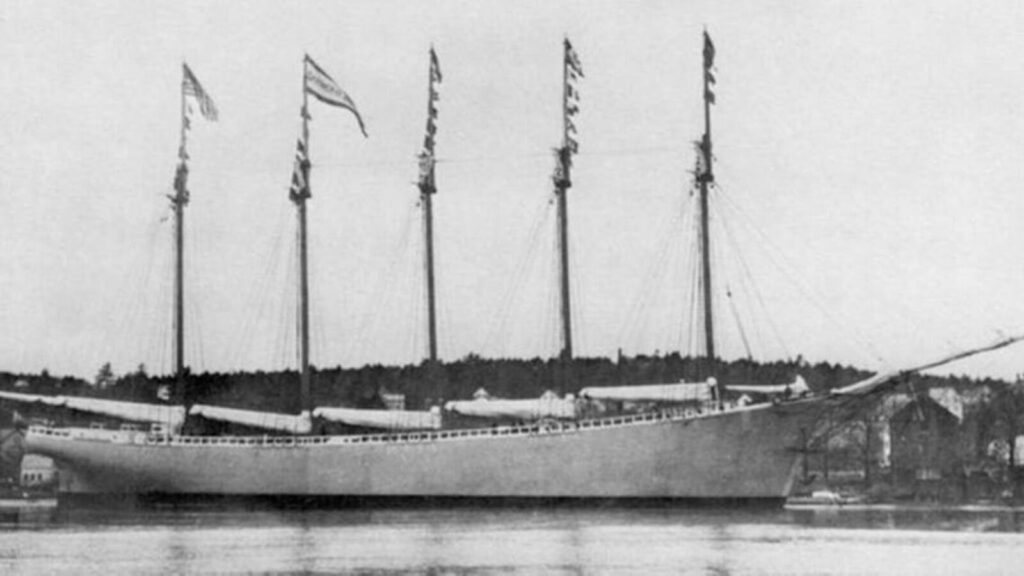

The Carroll A. Deering was built in 1919 in Bath, Maine, by the G.G. Deering Company. Owner Gardiner Deering named the ship for his youngest son, Carroll Atwood Deering, who worked as a bookkeeper for the company. The ship was the last ship ever built by the company and one of the last wooden sailing ships built in the world before steel took over.

The vessel was a large commercial sailing schooner, 1,879 tons, 225 feet long, 45 feet wide, with 5 masts and 3 decks. The Deering was “outfitted in the style of a passenger vessel, being trimmed in oak, ash, and mahogany, with a working lavatory, electricity, and even steam heat.” 1https://www.fishermensvoice.com/archives/202001TheCuriousCaseOfTheCarrollADeering.html

The Deering was in service for approximately 18 months and had several successful runs before whatever happened, happened. The original Captain was part-owner William H. Merritt, a World War I hero. Merritt was credited with saving the entire crew of his previous command, the Dorothy B. Barrett. The Barrett was attacked by a German U-boat in August 1918. William’s son, Sewall Merritt, was serving as first mate on the Deering. The engineer was named Herbert Bates. The rest of the 9-man crew was made up of Scandinavian men. The names of the crew members seem to have been unfortunately lost to time.

The Voyage Starts out Troubled

On August 22, 1920, the Deering left Norfolk, Virginia, bound for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to deliver a load of coal. After only a few days at sea, Captain Merritt fell seriously ill and was unable to continue. The ship reversed course to the Port of Lewes, Delaware. Both the captain and his son disembarked, leaving the ship without a captain or first mate. Little did either know that this change of course would save their lives.

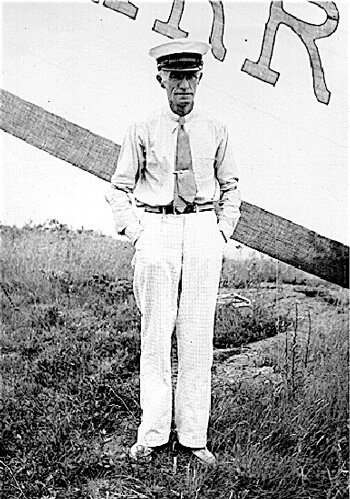

Captain Merritt telegraphed the G.G. Deering company, letting them know of his illness and inability to continue on with the voyage. He suggested that the company hire Willis B. Wormwell of Portland, Maine. They agreed, and soon Wormwell and Charles McLellan, who had been hired as first mate, met the Merritts at Hotel Rodney in Lewes. Bates stayed on as the ship’s engineer. The Deering resumed its journey to Brazil on September 8, 1920. Wormwell was 66 years old and well respected. He had over 25 years of experience. Not much has been reported about McLellan, other than he was Scottish.

The Voyage Continues

The Carroll A. Deering arrived in Brazil sometime in late November 1920. The cargo was delivered with no problems. Captain Wormwell granted the crew a few days off before they began the return trip. The Deering departed Brazil on December 2, 1920. Its next stop was Barbados to resupply. They departed, headed for Hampton Roads, Virginia, on or around January 9, 1921. The ship was now in ballast, which in maritime terminology means it was carrying no cargo. This would have made the return voyage quicker, as the ship would sit higher in the water and potentially be more susceptible to the wind. 2https://navalhistoria.com/deering/

The Disappearance that Captured a Nation

The last day the ship was seen before it was abandoned was on January 29, 1921. The Carroll A. Deering passed by the Cape Lookout Lightship. As it was passing by, a crew member communicated through a megaphone that the ship had lost both of its anchors and asked that the G.G. Deering Company in Maine be notified.

The man was described as being tall and thin with red hair, a thin nose, and a Scandinavian accent. He was definitely not Captain Wormwell. This was considered a breach of maritime protocol, which dictated only a ship’s captain or an officer be allowed to speak. According to the Cape Lookout lightship keeper, the crew was “milling aimlessly” about the deck, which was also very unusual.

The Carroll A. Deering was seen once more as it passed by the SS Lake Elon, a steamship, at approximately 5:45 p.m. on January 30th. The ship was seen “charting a peculiar course,” seemingly headed right for destruction on the Shoals.

The Treacherous Diamond Shoals

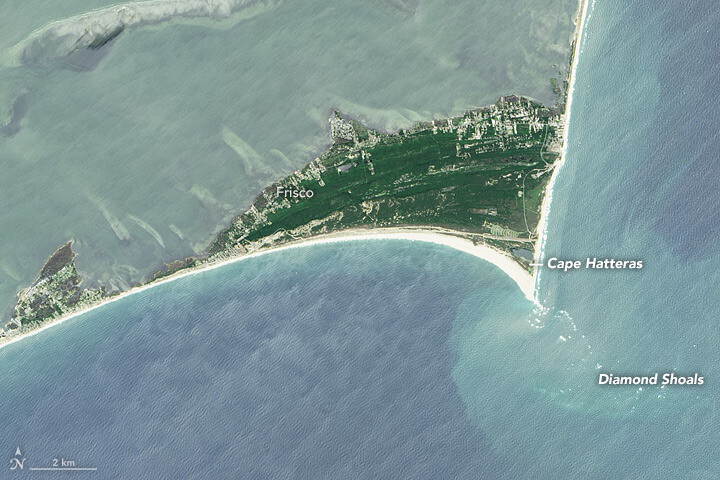

The Diamond Shoals are a group of submerged sandbars located off the coast of North Carolina, near Cape Hatteras. They are part of the larger system of shifting sandbars in the area known for its treacherous waters. The Shoals are located in the Outer Banks, an area famous for its maritime hazards, including unpredictable tides and strong currents. The Outer Banks are known as ‘The Graveyard of the Atlantic.’

At 6:30 a.m. on Monday, January 31, 1921, C.P. Brady of the Cape Hatteras Coast Guard Station spotted the Deering, aground on the Diamond Shoals. It was an eerie sight. The ship’s sails were set, the decks awash, lifeboat ropes were hanging down, and the waves were continuously breaking over the schooner, some as high as two or three stories. No sign of life was seen. No distress call had been made.

The seas were too rough and the waves too tumultuous for any rescue efforts to reach until the morning of February 4th. The wrecker Rescue, along with the cutter Manning, reached the battered ship around 9:30 am. Captain James Carlson of the Rescue boarded the ship and confirmed its identity as the Carroll A. Deering.

A Ghost Ship

According to the book Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals by Bland Simpson, the ship was found in the following condition:

The steering gear was ruined, the wheel itself was broken, and the binnacle box, which held the ship’s compass, was smashed in and shattered. A 9-pound sledgehammer was ominously propped up nearby. The ship’s rudder, which helps steer the ship, was disconnected about 15 feet from where it is usually attached, and the part that connects it to the ship was pushed up through the deck. It is impossible to say when the damages occurred, before or after the ship ran aground on the Shoals.

The sidelights and running lights were burned out. Two red lights attached to the highest point of the ship, which signal a ship in danger, were also burned out. No one who had come into contact with the Deering had reported seeing the lights burning.

In the chart room, an ocean chart lay spread out on a table. The ship’s nautical instruments, chronometer, logs, and papers were all gone. Captain Wormell’s handwritten log entries on the ship’s map were replaced with another hand after January 23.3https://islandfreepress.org/hatteras-island-features/the-outer-banks-carroll-a-deering-and-the-attempted-ghost-ship-coast-guard-rescue/

The ship’s two lifeboats, a small dory and a 24-foot yawl equipped with a 2-cylinder, 6-horsepower motor, were both gone. The wind had already torn two of the ship’s large sails. The ship’s two anchors were missing, as well as one of the chains. The only things left in the ship’s lazarette, or storage area, were water-soaked barrels, ropes, and sails.

The Disappearing Crew

Captain Wormwell’s cabin was found mostly intact; his bed was unmade, and his luggage trunk was missing. The crew’s quarters were similarly bare. A bed in a spare room off the Captain’s cabin looked as if it had been recently slept in. There were also several pairs of rubber boots lying around.

In the galley, or ship’s kitchen, the crew found a pot of pea soup, pans of sparerib slabs, and a pot of coffee. The food was remarkably well preserved, but this could’ve been because of the bitter cold temperatures. No obvious signs of struggle, blood, or items of torn clothing were found on the schooner.

Captain Wormwell’s Bible was found and handed over to his family. The cats found on board were taken to the wrecker, Rescue, and adopted by its steward, L.K. Smith.

The Search for the Vanishing Crew Begins

The search for the missing crew began in earnest. For ten days, Coast Guard vessels scoured hundreds of miles of ocean, coves, and beaches, seeking any trace of the 12 missing men. The searches produced nothing. No bodies or survivors were ever found. No wreckage from the lifeboats was found. There was no distress call recorded.

The Coast Guard was tasked with the initial investigation. They began by focusing on interviewing the last people to see the Carroll A. Deering, reviewing weather reports, and sea conditions, and collecting what little physical evidence they could. However, the investigation faced significant challenges. The absence of the crew and the ship’s log—vital for understanding the Deering’s last days—hampered the Coast Guard’s efforts. Still, they carefully documented the ship’s condition, noting the position of the sails, the state of the galley, and, of course, the missing lifeboats. Nearby coastal towns were searched for any sign of the missing captain and crew members.

The Government Steps In

Given the mysterious circumstances and the potential for foul play, the Federal Bureau of Investigation became involved. They started by completing background checks on Captain Wormwell, First Mate McLellan, and the crew. They were looking for any motives related to possible sabotage, mutiny, and connections to piracy. However, after an extensive investigation, the FBI did not uncover any substantial evidence to support these theories.

Investigators from the Department of Justice, U.S. Navy, U.S. Treasury, Department of Commerce, State Department, and the U.S. Shipping Board were all a part of the investigation at one time or another. Theories such as insurance fraud, bad weather, cargo piracy, and disputes over pay and treatment were all explored. Other theories, such as Russian Bolshevik pirates, rum-running during Prohibition, and political unrest, were also explored.

Mass suicide was also theorized but quickly shot down. Another theory was that the ship had picked up a “secret” cargo when it stopped in Barbados. The crew was killed when they dropped this cargo off, and the Deering was then sent adrift, with the ocean to decide its fate. No evidence of this was found.

Trouble at Sea

During the investigation, authorities discovered that there was unrest among the Carroll A. Deering’s captain and crew.

During the downtime in Rio de Janeiro, Captain Wormwell met with a friend of his, Captain Goodwin. Wormwell discussed his mistrust and disdain of his first mate and almost all of his crew. The only member he didn’t have a problem with was Bates, the engineer.

Then, while in Barbados, Charles McLellan complained to another ship’s captain, Hugh Norton of the Snow. McLellan said Wormwell undermined him when he tried to discipline the crew. He also complained that all the navigating was left up to him, due to Wormwell’s failing eyesight. McLellan, who would later be arrested for public drunkenness, was overheard saying, “I’ll get the captain before we get to Norfolk, I will.” 4Simpson. Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering Captain Wormwell ended up bailing McLellan out of jail, and the two once again boarded the Deering and headed for Virginia.

Message in a Bottle

In April 1921, a local fisherman named Christopher Columbus Gray found a message in a bottle. It read, “Deering captured by oil-burning boat something like (a) chaser, taking off everything, handcuffing crew. Crew hiding all over ship. No chance to make escape.”

In May 1921, with renewed hopes because of the letter, Captain Wormwell’s wife, Mrs. Wormell*, his daughter Lula N. Wormwell, Captain Merritt, and the Wormwell’s pastor Rev. Dr. Addison Lorimer visited Washington D.C. and convinced then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover to take over the investigation. Hoover would eventually put his right-hand man, Larry Richey, in charge.

Captain Wormwell’s daughter Lula is credited with pushing the government to investigate more thoroughly than they already had. Her emotional and determined involvement added to the public interest in the case. She was an important figure in advocating for answers and keeping the investigation in the public eye, especially during the early days.

Eight years before he would become president, Hoover summoned the ship’s owner, Gardiner Deering, Herbert Bates’ own mother, and three different handwriting experts to inspect the letter. All of them agreed that they believed the letter to have been written by Bates. Some contemporaneous newspapers report that Lula Wormwell herself traveled to the homes of each crew member to compare their handwriting to that of the note.

A Cruel Hoax

Unfortunately, it was determined that the only real piece of evidence regarding the Deering’s fate had been faked by the man who supposedly found it. Christopher Gray forged the note in the hopes that he could discredit the staff at the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and cause someone to be fired over the matter. He had previously applied for a position with the lighthouse service without success; he hoped the letter would create a job opening for him.

Gray admitted to studying Bates’ handwriting in order to make the forgery seem more legit No reports are available regarding any charges Gray may have faced.

Investigation Concluded, but not Closed

At the time, the search effort for the Deering’s crew was considered one of the largest and most complex in U.S. maritime history, given the vast area covered and the limited technology available for such operations.

The Coast Guard ended up concluding that the crew didn’t abandon the ship after it was stranded. The harsh shoals would have destroyed the lifeboats immediately, and some evidence of that would have been found. They posited that the crew would have lowered the sails prior to leaving to stabilize the ship, but who can really say what people would do if they believed their lives were in immediate danger?

Richey’s investigation ended in late 1922 without a statement or even an official finding. He and Hoover came to the conclusion that the Deering’s crew had mutinied in the face of a hurricane, which was reported in the area of Cape Hatteras at the same time as the Deering. No one could say with certainty if Wormwell’s problems with McLellan, or McLellan’s threat towards Wormwell, played a role in the disappearance of the crew. The investigation was never officially closed. And the mystery endures.

Theories about the Carroll A. Deering

Supernatural theories such as the Bermuda Triangle have been posited by some. Any regular watcher of 1980-1990s-era Unsolved Mysteries is familiar with the lore surrounding the triangle. The Bermuda Triangle is a roughly triangular area between Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and the Florida coast near Miami. A number of ships and aircraft have disappeared in the area under mysterious circumstances. It doesn’t seem as if the Deering is a victim of the triangle, based solely on where it ran aground.

“Unless it was pirates who carried off the crew of the schooner Carroll A. Deering, we are forced to the belief that the seas hold in their dark, unfathomed depths dangers for ships and the men who sail them of which we have never dreamed.”

-Hamlin Herald September 9,1921

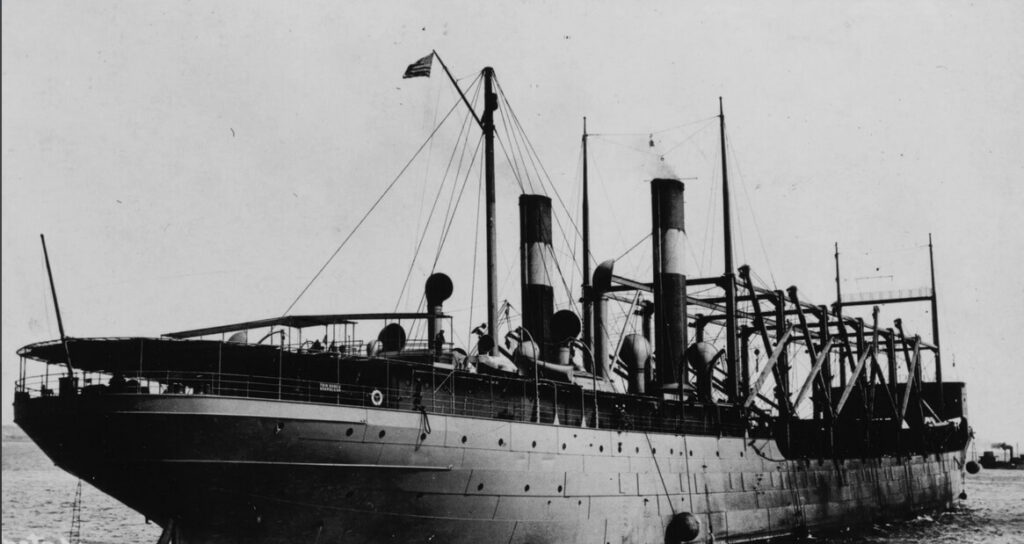

The U.S.S. Cyclops

Around the same time, other ships unexplainably vanished in the area, adding an eerie sense of intrigue to the mystery of the Carroll Deering. The U.S.S. Cyclops, named after a race of giants in Greek mythology, was a cargo ship designed to refuel other ships with coal. It was carrying a load of 10,973 tons of manganese ore, used to produce steel, when it disappeared. The Cyclops was on a return trip from Rio de Janeiro, just like the Deering when it disappeared.

The vessel was expected to arrive in Baltimore, Maryland, on or around March 13, 1918. It made an unplanned stop in Barbados on March 3rd and continued on its journey a day later. After this point, no one ever saw or heard from the Cyclops or any of its crew again. There was no distress call made, no SOS. As a matter of fact, its last transmission was ‘Weather Well, All Fair.’ The ship just disappeared into the wide expanse of the ocean.

There have never been any signs of the Cyclops found: no wreckage, no bodies, no floating cargo, nothing. In the more than a century since, nothing of the Cyclops has been found washed ashore. Three hundred and eight souls were lost. On June 1, 1918, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt declared Cyclops to be officially lost. Theories range from attack from a German U-boat, catastrophic structural failure, and bad weather. It is considered the largest non-combat loss in the U.S. Navy’s history.

The S.S. Hewitt

The other ship that disappeared was the S.S. Hewitt.It was last seen on January 20, 1921, just days before the Deering was found aground on the Shoals. The Hewitt was a steel-hulled bulk freighter. It was making its way from Sabine, Texas, to Portland, Maine, carrying a cargo of sulfur when it sent its last message on January 25th. It was last seen off the coast of Florida.

Neither the Hewitt nor any of its crew were ever found. 42 souls were lost. There is a theory that after inexplicably abandoning the Deering, its crew were picked up by the Hewitt. In a 1952 edition of the News and Observer, reporter Aycock Brown writes that a “tremendous flash and huge billow of smoke” were reported off the coast of New Jersey. He posited that the explosion could have been that of the Hewitt, and if the Deering crew were on board, they would have perished as well.

The Aftermath

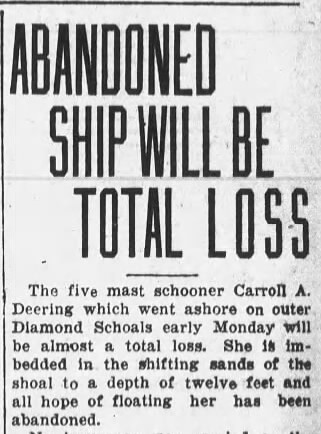

The Carroll A. Deering was eventually declared a loss. It was valued at $275,000, which would be around $4.5 million dollars in 2024. Crews salvaged what they could out of what was left. The wreckage was eventually pulled out into the ocean and dynamited. Some of the ship’s wreckage washed ashore on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, where it remained visible for more than 30 years. The ship’s bell and capstan are on display at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, North Carolina.

A Century of Silence on The Carroll A. Deering

Now, over a century later, the fate of the Carroll A. Deering continues to haunt the waters of the Atlantic.

Why did the captain and crew abandon a perfectly good ship? It would have made more sense to shelter in the possibly malfunctioning ship, send out a distress call, and wait for rescue, rather than face certain death in the freezing ocean waters.

As maritime experts and historians reflect on this unsolved mystery, the disappearance of the Carroll A. Deering serves as a chilling reminder of the vast unknowns that still exist in the world’s oceans—and the many questions that may never be answered. The Carroll A. Deering remains an enduring unsolved maritime mystery.

Sources:

The New Sea Mystery. (9/9/1921). The Hamlin Herald.

The Most Amazing Sea Mystery of all Time. (7/24/1921). The Minneapolis Journal.

Washington Bureau. Three U.S. Ships Vanish at Sea with Crews. (6/21/1921). New York Tribune.

International News Service. Loss of Ships Laid to Pirates. (6/21/1921). Times Herald.

The Log: The Ghost Ship Carroll A. Deering

Wikipedia – Carroll A. Deering

Library of Congress – The Carroll A. Deering

National Park Service – Carroll A. Deering

Coast Guard – Carroll A. Deering

*Captain Wormwell’s wife is listed as Lula Wormwell in several contemporaneous publications. His daughter is also listed as being named Lula. It’s unclear if they shared the same first name or if this was an error. I have chosen to refer to Captain Wormwell’s wife as Mrs. Wormwell and his daughter as Lula.

- 1https://www.fishermensvoice.com/archives/202001TheCuriousCaseOfTheCarrollADeering.html

- 2https://navalhistoria.com/deering/

- 3https://islandfreepress.org/hatteras-island-features/the-outer-banks-carroll-a-deering-and-the-attempted-ghost-ship-coast-guard-rescue/

- 4Simpson. Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering

Dive Deeper

Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering by Bland Simpson

Island History: The attempted rescues of the famous Outer Banks Ghost Ship, the Carroll A. Deering. Written by James D. Charlet, this gives an extremely detailed story of the Deering’s discovery and recovery.

Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic by James D Charlet

Lawrence Richey’s files on the Deering investigation are preserved in the Lawrence Richey Papers at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum in West Branch, Iowa

The Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum

Historical Blindness Podcast: Ghost Ship of Cape Hatteras

The Prosecutors Podcast: The Disappearance of the U.S.S. Cyclops

you found my ship if it still in good shape can you bring it san Francisco harbor thanks for finding it. when my men and I got knocked of it we thought we lost it but my crew passed away and I was only 15 when I got knocked off